Larches and Stones

Five larch seedlings, concrete cast, stones, soil

Deviant growth of larches can be traced, among other factors, to the burden caused by heavy snow, the extended snowmelt, and the overlapping growth period in high-elevation mountain areas. Trees are forced into whimsical forms. Loderer uses the pressure and weight of stones and concrete to force young tree saplings into unnatural shapes. At Kunsthaus unique sculptures for the interior space are on display.

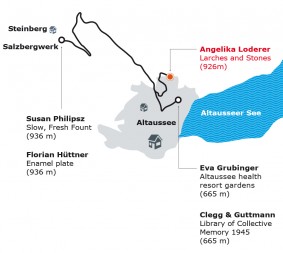

IN THE VALLEY

The outlook here used to be known as the “Artist’s Panorama.” The Kerry Villa at the foot of the Loser belonged to the Jewish artist Christel Kerry. Her father had built the house in 1896, the highest-lying villa in Altaussee. From this height there is a magnificent vista of the valley flooded with light, its idyllic health resort, and on to Lake Altaussee and the distant Dachstein mountain. The first American soldiers came across the Pötschen Pass that you can almost make out in the north-west on 9 May 1945 to liberate Altaussee.

The outlook here used to be known as the “Artist’s Panorama.” The Kerry Villa at the foot of the Loser belonged to the Jewish artist Christel Kerry. Her father had built the house in 1896, the highest-lying villa in Altaussee. From this height there is a magnificent vista of the valley flooded with light, its idyllic health resort, and on to Lake Altaussee and the distant Dachstein mountain. The first American soldiers came across the Pötschen Pass that you can almost make out in the north-west on 9 May 1945 to liberate Altaussee.

In 1938, like many other Jews, Christel Kerry’s property was seized, but she was given a kind of pass allowing her to stay in the town with her daughter, with the SS quartered in her villa. The SS and the Gestapo maintained a high level of pressure in persecuting people throughout the region. There were several raids and many searches. In April 1945, they were joined by Ernst Kaltenbrunner, head of the Reichssicherheitshauptamt at that time. His young mistress, Countess Gisela von Westarp, had been living there since the fall. She had given birth to her two twins in Aussee. Kaltenbrunner tried to get away unscathed in the chaos of the final days of the war, having large quantities of gold, coins and foreign currencies buried to this end. He was captured on the Wildensee Alm on 12 April 1945 with the aid of several resistance men and executed one year later in Nuremberg.

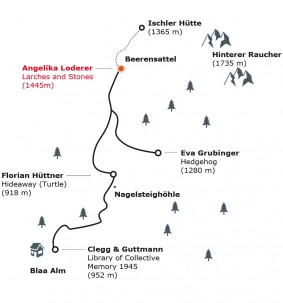

ON THE MOUNTAINS

Today the provincial border between Styria and Upper Austria runs across the Ahornkogel (1401m) alongside the Beerensattel. The Schwarzenberganger continues to be used as a pasture to this day. Here, high up in the mountains, only larches and other coniferous trees are able to survive. The slope used to be densely wooded but was considerably thinned out by hurricane Kyrill in 2007.

Today the provincial border between Styria and Upper Austria runs across the Ahornkogel (1401m) alongside the Beerensattel. The Schwarzenberganger continues to be used as a pasture to this day. Here, high up in the mountains, only larches and other coniferous trees are able to survive. The slope used to be densely wooded but was considerably thinned out by hurricane Kyrill in 2007.

The Igel was located about 120 meters below the Beerensattel. Towards the end of their regime the Nazis intensified their efforts to persecute political opponents in the form of house searches and raids. Again and again, people sought shelter in secluded huts or on mountain pastures. Many of them were afraid that their hideouts might be given away; supporting them was extremely dangerous. The people who operated the Blaa Alm mountain lodge and the Ischler Hütte mountain hut at that time were reputed to be Nazi sympathizers. Nevertheless, supplies for members of the resistance movement in the Igel were stored not far from the Rettenbachalm and the Blaa Alm. Women such as Maria Plieseis, Leni Egger and Marianne Feldhammer, a small number of mountain farmers and other supporters provided the men with information, fresh food and, in one case, with a weapon. Poached game was exchanged for smoked meat. As one of the few women who climbed mountains at that time, Marianne Feldhammer was the only woman to know the way up to the Igel from Altaussee via the Naglsteig.

ABOUT THE WORK

This Styrian sculptor turns techniques, materials, and forms of sculptural design into the theme of her art.

Draining, pouring, casting, ladling, layering, and pressing – as practiced in skilled crafts and trades – are translated by the artist into free forms ranging from abstract to non-representational. Assuming that we were encased in history today like a frozen flash of lightening, caught in a moment in time, then we would repeatedly encounter über-historical phenomena and events that could liberate us from the burden of such human constraint. Research and art are two such methods that attempt a practical approach to staying clear of history’s pitfalls. Certain artists tend to experiment with well-known techniques, discovering new paths in the process and venturing risks with montage or recontextualisation. Angelika Loderer counts among these curious individuals – well trained in the canon of manual dexterity – who uncover moments of playful experimentation that eschew any given function yet without succumbing to the empty beauty of autotelic form. She takes the quartz sand used in bronze casting and presses it to create material collages in combination with found items from everyday life (Untitled, 2013) or with fragments from other works of art (Untitled [With Dejan Dukic], 2014). She makes moulds of fragile mole burrows (Schüttlöcher, 2012) or rough woodpecker cavities (Untitled [Buntspecht I-III], 2013) and casts them in bronze, displaying a breathtaking complexity of detail. Or she fashions Death Masks from grass, which slowly rot from the inside out, furnished with a layer of plaster (Untitled [Totenmasken], 2014).

Draining, pouring, casting, ladling, layering, and pressing – as practiced in skilled crafts and trades – are translated by the artist into free forms ranging from abstract to non-representational. Assuming that we were encased in history today like a frozen flash of lightening, caught in a moment in time, then we would repeatedly encounter über-historical phenomena and events that could liberate us from the burden of such human constraint. Research and art are two such methods that attempt a practical approach to staying clear of history’s pitfalls. Certain artists tend to experiment with well-known techniques, discovering new paths in the process and venturing risks with montage or recontextualisation. Angelika Loderer counts among these curious individuals – well trained in the canon of manual dexterity – who uncover moments of playful experimentation that eschew any given function yet without succumbing to the empty beauty of autotelic form. She takes the quartz sand used in bronze casting and presses it to create material collages in combination with found items from everyday life (Untitled, 2013) or with fragments from other works of art (Untitled [With Dejan Dukic], 2014). She makes moulds of fragile mole burrows (Schüttlöcher, 2012) or rough woodpecker cavities (Untitled [Buntspecht I-III], 2013) and casts them in bronze, displaying a breathtaking complexity of detail. Or she fashions Death Masks from grass, which slowly rot from the inside out, furnished with a layer of plaster (Untitled [Totenmasken], 2014).

The landscape and social history of the Ausseerland region have inspired Loderer to work with pressure and gravity – with material pressure that can cause larch trees to exhibit strange deformations starting at about 900 meters above sea level and extending up to the treeline. Such deviant growth can be traced, among other factors, to the burden caused by heavy snow, the extended snowmelt, and the overlapping growth period in high-elevation mountain areas. Young trees are forced into whimsical forms. In her installation, Loderer for instance uses the weight of stones to coerce young tree saplings into unnatural shapes. Her natural sculptures allude to civil and political development in the region and also to the inhumane repercussions of the persecution practices pursued by a totalitarian regime, which left behind clear (though not immediately discernible) traces both in the valley and the highlands.