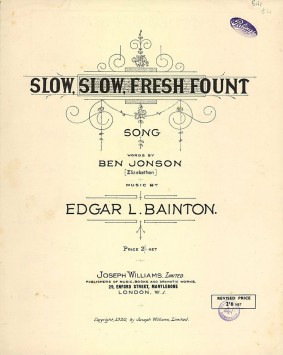

Slow, Fresh Fount

Audio installation with vocals of “Slow, Slow, Fresh Fount” (1601) by the English poet Ben Jonson, set to a tune by William Horsley, and reworked by the artist

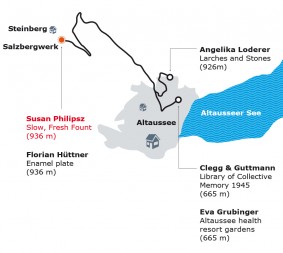

In Kunsthaus Graz temporarily raises a lament, which also resonates in the Altaussee salt mines – an ancient historical mining site that before the end of the war briefly served as one of several storage facilities for art looted by the National Socialists. The same elegy from the sixteenth-century resonates throughout the space on the banks of the legendary Toplitz lake. The nymph Echo laments her rejection by Narcissus and sheds salty tears.

IN THE VALLEY

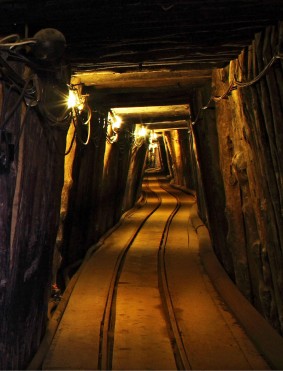

As of January 1945, the salt mine not only contained valuable salt deposits but also, deep down in the Kaiser-Franz-Josef-Werk and the Kammergrafen-Werk workings, priceless works of art intended for display at the Führermuseum in Linz – a museum that was, however, never built. An inventory lists 6577 paintings, 954 prints, up to 1700 crates of books and packages, sculptures, baskets and hundreds of other cases. In late 1944, the galleries had been enlarged and shored up despite the acute shortage of materials and timber. The repository contained holdings taken from several Viennese museums, “Aryanized” private collections and artworks looted from all across Europe, among them invaluable items such as the Ghent Altarpiece by the brothers Van Eyck, Michelangelo’s Madonna of Bruges, paintings by Rembrandt, Breughel and many others. Art experts were tasked with preserving and inventorying the paintings, prints and objects for which the constant climate deep down in the salt mine proved to be ideal, in spite of the fact that they had been plundered ruthlessly.

As of January 1945, the salt mine not only contained valuable salt deposits but also, deep down in the Kaiser-Franz-Josef-Werk and the Kammergrafen-Werk workings, priceless works of art intended for display at the Führermuseum in Linz – a museum that was, however, never built. An inventory lists 6577 paintings, 954 prints, up to 1700 crates of books and packages, sculptures, baskets and hundreds of other cases. In late 1944, the galleries had been enlarged and shored up despite the acute shortage of materials and timber. The repository contained holdings taken from several Viennese museums, “Aryanized” private collections and artworks looted from all across Europe, among them invaluable items such as the Ghent Altarpiece by the brothers Van Eyck, Michelangelo’s Madonna of Bruges, paintings by Rembrandt, Breughel and many others. Art experts were tasked with preserving and inventorying the paintings, prints and objects for which the constant climate deep down in the salt mine proved to be ideal, in spite of the fact that they had been plundered ruthlessly.

On 19 March, 1945, shortly before committing suicide, Hitler issued the infamous Nero Decree commanding the complete destruction of the Third Reich. Following this order, on 13 April, 1945 August Eigruber, the Gauleiter of Linz, arranged for several crates filled with unexploded aerial bombs dropped by the Allies to be taken into the salt mines. Some of the miners, however, opposed the imminent destruction of the mine, among other things for fear of losing their jobs. On the night of 3 May, they carried out a spectacular operation to remove the bombs from the galleries. In the end, only the entrance was blown up.

ON THE MOUNTAINS

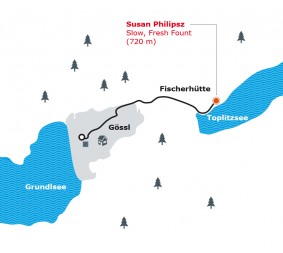

A mystical lake located at the end of the valley. This is where the Traun river rises and flows through the Toplitzsee. The lake is 100 meters deep and almost entirely enclosed by the steep rock faces of the Totes Gebirge. The Vordernbach stream cascades down the Teufelsgraben as a waterfall, as does the Hinterbach stream. The lake is fed by waterfalls and an underground stream from the Kammersee. Where it is over 20 meters deep, the water is free of oxygen. The large number of fallen trees makes diving here dangerous – several lives have been lost in this way. The still water creates a somewhat eerie and yet fascinatingly romantic impression.

A mystical lake located at the end of the valley. This is where the Traun river rises and flows through the Toplitzsee. The lake is 100 meters deep and almost entirely enclosed by the steep rock faces of the Totes Gebirge. The Vordernbach stream cascades down the Teufelsgraben as a waterfall, as does the Hinterbach stream. The lake is fed by waterfalls and an underground stream from the Kammersee. Where it is over 20 meters deep, the water is free of oxygen. The large number of fallen trees makes diving here dangerous – several lives have been lost in this way. The still water creates a somewhat eerie and yet fascinatingly romantic impression.

In 1819 Archduke Johann of Austria met the love of his life here: the commoner Anna Plochl from Aussee, who was later to become the Countess of Meran. An enchanting and romantic story. But the unfathomable lake has many different faces and has inspired a multitude of legends. There were rumors that the Nazis had hidden secret treasures in its depths. However, what they had really concealed was not a golden horde but instead some printing-plates for English pound notes and counterfeit money left over from Operation Bernhard. This plan, one of the largest ever government-organized counterfeiting operations, was designed to ruin the United Kingdom’s economy. The perfectly crafted dud notes were produced by Sachsenhausen concentration camp prisoners with the help of professional counterfeiters. During the war, from 1943 to 1945, the Toplitzsee was also the scene of a number of weapon technology experiments carried out by the German navy.

In 1819 Archduke Johann of Austria met the love of his life here: the commoner Anna Plochl from Aussee, who was later to become the Countess of Meran. An enchanting and romantic story. But the unfathomable lake has many different faces and has inspired a multitude of legends. There were rumors that the Nazis had hidden secret treasures in its depths. However, what they had really concealed was not a golden horde but instead some printing-plates for English pound notes and counterfeit money left over from Operation Bernhard. This plan, one of the largest ever government-organized counterfeiting operations, was designed to ruin the United Kingdom’s economy. The perfectly crafted dud notes were produced by Sachsenhausen concentration camp prisoners with the help of professional counterfeiters. During the war, from 1943 to 1945, the Toplitzsee was also the scene of a number of weapon technology experiments carried out by the German navy.

ABOUT THE WORK

Voice, sound, singing, tones, and related environments comprise the sculptural material of Susan Philipsz, who works to define spaces through sound.

Her installations establish connections to the setting in which they are audible, and they provide a new context for songs or sounds that are frequently of historical nature. Philipsz uses multitrack technology to transform comprehensive research on musical, literary, and historical models into new sound pieces. On the one hand, the artist invokes her own untrained singing voice, such as in Münster with a song based on E.T.A. Hoffmann, The Lost Reflection, 2007, or in Glasgow (her hometown), where she tonally activated the hollow space under three bridges along the River Clyde with vocal scores in 2010.

Her installations establish connections to the setting in which they are audible, and they provide a new context for songs or sounds that are frequently of historical nature. Philipsz uses multitrack technology to transform comprehensive research on musical, literary, and historical models into new sound pieces. On the one hand, the artist invokes her own untrained singing voice, such as in Münster with a song based on E.T.A. Hoffmann, The Lost Reflection, 2007, or in Glasgow (her hometown), where she tonally activated the hollow space under three bridges along the River Clyde with vocal scores in 2010.

In 2012 in Kassel, on the other hand, she disaggregated the Study for String Orchestra by Pavel Haas into sequences of sound. Haas’s composition was originally composed in 1943 at the Theresienstadt concentration camp; the original score was lost and later reconstructed. At dOCUMENTA (13), Philipsz distributed the different audio tracks featuring the individual instruments to the seven loudspeakers situated towards the end of the railway platforms at Kassel’s central train station. This site had been the departure point for many deportation trains travelling to the extermination camp. The new sounds were just fragments of the score and blended with the everyday sounds populating the environment. The sounds thus activated both the individual power of imagination and collective memory, eliciting a heightened mindfulness of the site. The art of Susan Philipsz “sits at a point where music becomes a kind of intangible sculptural material – or a material that points, often melancholically but not dogmatically, to absent bodies, absent objects“1

In the Altaussee salt mines – an ancient historical mining site that briefly served as one of several storage facilities for art looted by the National Socialists – Susan Philipsz will allow a two-voiced elegy from the year 1601 to resonate throughout the space. Its sound correlates with an installation playing at a nearby lake in the Ausseerland region.

–––––

1 Martin Herbert: „String Theories. On Susan Philipsz“, in: Ders.: The Uncertainty Principle. Berlin 2014.